Our website was created to help the family members of those who died and participated in Exercise Tiger. Dean Small, son of the late Ken Small, continues with his father's legacy. We are endorsed by the survivors and the families.

Alexander Z "Jerry" Brown Story - LST 507

Surviving Officers from LST 507 & 531

Ensign Alexander Brown, Far Left, Standing

(Deceased August, 1995)

(Also pictured, Ensign Douglas Harlander, LST 531, kneeling middle; and Dr. Eugene Eckstam, LST 507, far right, standing)

Jerry Brown's Story, written by Dan Tracy,

with permission by Brenda Brown Holson and the Brown Family

Alexander Z Brown had just graduated from the University of Florida when he signed up for World War II at a Jacksonville U.S. Navy recruiting station on April 30, 1942. He was slender, weighing 150 pounds and standing 5 foot 10, with blue eyes and brown hair. His complexion was listed as ruddy on his enlistment papers. A star athlete who lettered in football, basketball and baseball at his Winter Garden, Fl. high school, he went by the nickname Jerry, after a character in a popular comic strip called Jerry On The Job.

He entered the Navy as an apprentice seaman, Class V-7. His pay was $21 a month and, initially, he was considered a member of the Naval Reserve. After months of training, he entered active duty and was posted to the LST 507, the initials LST being the Navy acronym for Landing Ship, Tanks. Sailors disparaged the vessels as Large, Slow Targets.

On the evening of April 27, 1944, a joint command of the British and Americans staged a mock invasion of Slapton Sands, substituting for Utah Beach at Normandy. They sent a flotilla of eight LSTs — including the 507 — into the English Channel to simulate the crossing they would endure on D-Day.

Fully loaded with soldiers and equipment, the LSTs were supposed to return to Slapton Sands during the early morning, emptying the men, trucks, tanks and various paraphernalia onto the beach. They were to be greeted with live ammunition fired over their heads to give them an idea of the deafening noise, mayhem and resistance they would face.

The 507 carried almost 500 soldiers and sailors, plus it was jammed with amphibious DUKWs (six-wheel armored vehicle capable of floating), jeeps, tanks and trucks in the cargo hold. The 507 was in a second group of three LSTs, last in line. Another group of five left from nearby Plymouth. They met up in the channel.

The atmosphere aboard the 507 was lax, almost like a cruise, according to first-person and published accounts.

Four German E-boats, on random patrol, picked up on the radio traffic between the Allied ships and quickly moved into position. The attack began shortly after 1 a.m., April 28. At first, the Americans were slow to react, thinking tracer bullets they saw streaking across the sky were part of the practice run. But soon enough, they knew they were in trouble. They were 18 miles from port.

Brown was in the wheelhouse with the captain of the ship, Lt. James Swarts, who would die that night. Brown later wrote a letter in long hand describing what happened to the father of Swarts. The paper is yellowed now and crinkly to the touch, but the black ink remains legible. Words and sentences sometimes are crossed out as Brown tried to find the right phrase or best way to ease the undoubtedly anguished mind of the elder Swarts.

“At the time we were hit,” Brown wrote, “the Captain was on his bridge. He stayed there giving orders and doing everything that could possibly have been done to save his ship, until flames drove him to the stern. When it became apparent that nothing else could be done, he gave the order and personally directed abandon ship.”

Brown did not mention his role during the chaos of the ship sinking, though he certainly played a part in trying to keep panic among the crew and soldiers from spreading while at the side of Swarts.

“I can assure you that through his guidance, there was an orderly abandon ship. The confidence shown him by the men in this extreme emergency is unbelievable,” Brown wrote.

Before long, Brown continued, the only men left on board were himself, Swarts, two officers and two wounded soldiers. Swarts, “without hesitating or without thought of his own life,” gave his life jacket to one of the wounded, according to Brown. Left out of his account is the fact that Brown also gave away his life jacket to another. That was one of the few details he shared about Exercise Tiger with his family.

Swarts then went about the sinking, smoke-filled, burning vessel to make sure no one was still on board. He saw none. “In true Navy tradition,” Brown wrote, “and being the captain that he was, he abandoned ship, the last person to leave.”

Once in the black, mercilessly cold water, Brown, Swarts and others saw a raft, but it was near a slick of burning oil and gasoline. Another ensign, Frederick O. Beattie, swam under the flames, and retrieved the raft, Brown wrote. The wounded were placed in the raft, while the able-bodied clung to its sides.

“Had he not done this,” Brown wrote of Beattie, “I am sure none of us would have survived.”

The book Exercise Tiger by Nigel Lewis recounts how Brown tried to paddle the raft retrieved by Beattie. “He was on a side,” the book said of Brown. “Two were inside, with five others holding on. They were spotted by a shipmate, Tom Clark, who was clinging to a piece of wood.”

“That you, Brownie?” Clark asked.

“Yes.”

“Have you got the captain?”

“Yes, he’s here, Tommy.”

“Got room for one more?”

“Damn tootin’, come on over.”

After an hour in the icy water — its temperature was about 42 degrees — 11 men had collected around the raft, Brown wrote.

“From then on,” Brown’s letter said, “it was a matter of waiting.”

Time, however, was not an ally.

By around 4 a.m., a fog rolled in, the air acrid, stinking of smoke and burning fuel. The sea was bobbing with corpses wearing life jackets, many face down in the water because they had not put them on properly due to a lack of training. It was eerily quiet, a stark contrast to the cries, screams and concussive sounds of battle that had filled the air earlier.

Brown and his group were rescued by the LST 515, which had doubled back for survivors, even though the ship was supposed to head for shore in case of an attack. The Exercise Tiger website credits the 515 with saving 134 men from the freezing water.

“The captain died from exposure shortly after he was taken aboard the rescue vessel,” Brown wrote. “Although I was receiving medical attention myself, I know that every possible thing was done to save his life. I think that under the circumstances there was nothing that he or anyone else could have done to prevent his death.”

In his letter, Brown tried to console Swarts’ father by saying his son’s death was “not unpleasant. When we first entered the water, it was very cold, but then we got used to it. You could feel your strength wane. The end is very easy, without any suffering.”

Brown also wrote that Swarts had the respect of every man on the LST 507: “It is impossible for me to explain my feelings toward the captain…He met and dealt with every problem fairly and squarely…He commanded a happy ship.”

Brown wrote a second letter as well, this one to the wife and son of another fallen comrade that he referred to only by his first name. “I have thought of you both quite often since that tragic night,” he wrote to Dottie and Donnie. “I think it is needless to say that Chief Ken was my best friend aboard.” There are two Navy men from the 507 listed as dying during Exercise Tiger with the first name of Ken; one whose last name was Smith, the other Scott.

After the torpedo struck the 507, Brown said he lost track of Ken, “but I do know that he was not wounded and got off the ship without injury. His death was caused by exposure.”

Ken’s death, Brown wrote, in the same way as Swarts. It was not “unpleasant…At first you are cold, but from then on you become used to it and the end is like going asleep. The few of us that were saved were extremely lucky.”

Brown then addressed Ken’s son: “Donnie, your father was a great man. He was well liked by everyone that he met. There was absolutely nothing that his men wouldn’t have done for him. He had great visions for you and knew that in being his son you will not disappoint him.”

After being taken ashore, Brown was examined by an Army doctor and pronounced fit, with one minor exception. According to Brown family lore, one doctor told Brown he likely was sterile after spending so much time in the frigid Channel water. Brown, who would pose in borrowed clothes for a black and white photo with other 507 survivors shortly after the exam (see photo at top), would prove the doctor wrong in coming years. His future wife Caroline Peters would bear five of his children, two girls and three boys.

Swarts’ and Chief Ken’s remains were transported to the Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey, about 30 miles southwest of London. Swarts later was reinterred at Fort Bliss National Cemetery in El Paso, Texas, at the request of his father, a Van Horn, Texas, attorney also named Jim.

The elder Swarts wrote back to Brown, thanking him for the letter, “which was splendid in its detail, but also your friendship for our boy who has gone on ahead…(W)ho knows, but God, what is best and He has spoken and I am ready to accept his wisdom, though the purpose is not plain.”

Brown had to wait more than three months after Exercise Tiger to write Swarts’ father and Ken’s wife and son because the military ordered all survivors to tell no one of what happened. Brown, in his letter, blamed the delay on “pending operations” and was purposely vague on many of the details of that night.

Like his Navy mates, Brown was not allowed to attend the burial services for their deceased friends at Brookwood Cemetery. Instead, they went to a memorial May 1, Brown wrote, likely held in the South Hams, and led by an Army chaplain.

By D-Day, Brown was reassigned as a gunnery officer on a mine sweeper, the USS Staff, and was on the water at Utah Beach when the invasion started. The Staff was the lead minesweeper for the battle.

Brown stayed with the Staff until April of 1945, when he was transferred to another minesweeper, the USS Deft. In addition to his gunnery officer duties, he was put in charge of benefits and insurance for the Deft crew, records show. The Deft was steaming towards Japan when atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

On February, 28, 1946, Ensign Brown was granted an honorable discharge from the Navy, though he would remain on inactive reserve until August, 1955. He died of congestive heart failure in 1995. He was 73. His wife passed away in 2007 at the age of 86, a victim of brain cancer.

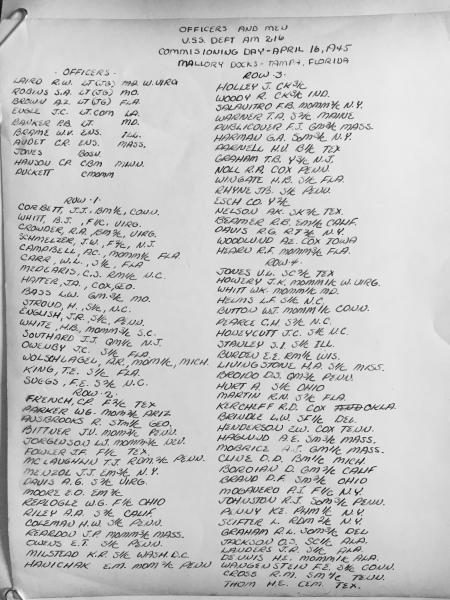

Mine Sweeper USS Deft

Crew of the USS Deft

Jerry Brown is in the Front Row, Third from Left

Names of the Crew of the USS Deft